As Montreal celebrates the 375th anniversary of its “founding,” Cinema Politica’s Stefan Christoff interviewed Inuk visual artist Stephen Puskas about Inuit cultural resistance to colonialism in Québec in 2017. In this interview, Stephen confronts the comfortable truth* that anyone can take Inuit land, culture and stories. As some Canadian mediamakers celebrate the creation of an “Appropriation Prize,” this interview is especially urgent in its powerful challenge of the corporate cultural appropriation of Inuit cultural symbols.

Read the interview or listen to it recorded below!

Stephen Puskas is a visual artist, filmmaker and researcher who recently finished work as a project manager for Nunalijjuaq and producer for Montreal’s Inuit radio show Nipivut.

//

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Stefan Christoff : I am sitting with Stephen Puskas who is a visual artist and researcher. Today we are having a discussion as part of the Comfortable Truths project that was initiated by Cinema Politica and today we will be focusing on the representation of Inuit cultural symbols and culture that is taking place today, whether by businesses, or different institutions that are non-Inuit, yes, so there’s a lot of talk about, given that you have worked a lot on different specific cases around these issues. Thanks for speaking with us.

Stephen Puskas : Thank you very much for having me.

Appreciate it. As a starting point, so for you if we are looking at the ways that different corporate products and projects have represented Inuit cultural symbols, or language, here in Quebec, but also beyond, could you speak your truth in regards to the way that you have addressed this issue publicly over the last few years ?

One way that I have addressed this publicly is when I notice things that have happened around advertisements, or business names, logos and such, that use Inuit identity, or Inuit culture, as their corporate identity. I question that and openly ask questions about this. Why is this happening ? If this does use Inuit, then how can Inuit benefit from this ? One example is Ungava Gin, which uses Inuit syllabics, they’ve made cartoon depictions of Inuit mascots, they’ve had girls wearing skimpy parkas at trade shows, to advertise their product and they claim that the botanicals that they use come from the north, from Inuit territory, but we can’t find any evidence that they do. That’s one example.

Another example that I have talked about recently is Igloofest, well it may seem benign that they use an Inuktitut word, meaning house, or home, like a snow house, as a name for a festival, but when you look at their advertizing, they are really pushing a fantasy, you know, the cold, the arctic, the north. This year they had commercials and posters all around this city of penguins, crowds of penguins dancing, sitting on speakers and stuff, or penguin DJs, but the reality is that penguins live in Antarctica, they don’t live in the north. So what I find is that the fantasy, about Inuit, or the fantasy about the north, is more prevalent, more present and more subversive in our day-to-day lives than the reality. I think that the danger with that, the damage it does is that it mis-educates the general public, about their own country, about people that live in their own country and about their own environment.

These symbols, you mentioned Igloofest, which is a major cultural event in Montreal, we are sitting right now at the Bibliothèque Nationale in downtown, at the cafe and these symbols, whether it’s Igloofest, you were also talking about Ungava Gin, which you addressed publicly, these types symbols are prominent in public space, whereas actual Intuit symbols, cultural representation, is obviously a lot less prominent, in terms of major product, but also in terms of cultural events. Could you talk about this dichotomy, in terms of the sustained and continuous utilization of these symbols, but then very little support, or public recognition of actual Inuit culture and voices within public space in Montreal, or in Quebec.

At least regarding Montreal, the Inuit, many groups and people, have been asking for at least 20 years to have a cultural centre, a community centre here, a place for people to gather and that call, that request has come unanswered. What’s even worse is actual places like Villeray, back in 2010, there was what was referred to as the Villeray incident, because at that time Makivik, the Inuit corporation in Quebec, put a bid in to buy an old Chinese hospital, that was closed and to re-open it and the locals, residents in Villeray, started circulating a petition and flyers, the flyer claimed that Inuit would ‘pisse dans la rue’ and the petition was mainly to block Makivik from buying the hospital, the petition was mainly implying that Inuit weren’t welcome in the neighborhood, saying things like the presence of Inuit in the neighborhood would increase prostitution, crime and drug use, violence in the neighborhood and in the streets, so for homeowners that would drive down their real estate value.

Even Ami Sampson, the mayor, who is part of Denis Coderre’s equip, basically said in the media that Inuit weren’t welcome in the neighbourhood. So for a city that is so multicultural, it’s also a city that is very segregated and it’s also a place where Inuit are often pushed out of areas. Even around Cabot square, around Atwater metro, the city of Montreal made a unilateral decision to renovate the square, which has long been an important meeting place for Inuit and when they released the plans about the renovation, it was a place where no one could lay down, they had benches, but benches were no one could lay down. It was designed as a place where people could walk through, not to stay around, the city really wanted to dissuade people from staying in the square and I think that’s because a lot of the Inuit in the area are visiting from the YMCA.

Also a lot of Inuit who come to Montreal for medical care ?

Yes a lot of Inuit who come for medical care, so I guess for a lot of people that’s a depressing image to have around them and that became another stereotype that was developed here overtime. A stereotype of Inuit as homeless, as drunks, as prostitutes, things like that, stereotypes that targeted Inuit as a ‘problem’ basically. So it seemed that there are these two extremes, one of this fantasy Inuk, this noble savage, wearing a parka, hunting with a harpoon, you know, chumming it up with polar bears, penguins and things like that.

Penguins, which are non-existent in the regions that are indigenous to Inuit …

Exactly. I actually was collecting for a while images of Inuit, with penguins, with cartoon polar bears, around Igloos, around Inuksuit, so I was collecting a lot of that, so I see that there are these two polar opposite depictions of us and I don’t think that’s the reality, like sure, homelessness is an issue, with the Inuit community in Montreal, a serious issue, but that’s not the majority of the Inuit community here. The problem here is that homeless people, generally, are a lot more visible in the city, they are there on the streets, but it’s much less likely that you are going to see an Inuk on the streets when they are going to and from work, or they are going from work to go home. One of my friends who’s an Inuk journalist was saying to me that many people can identity Inuk on the streets, but they can’t identify me as an Inuk when I am walking out on the street, because I got a job, or because I have a home, it’s as if that version of us doesn’t exist in this culture here.

There are issues of social crisis that face people living in the city, living close to the street, or living with severe poverty, which obviously haven’t thoroughly been addressed, there’s a colonial context to that …

Yes, well I mean the context here in Quebec was that, you know, Quebec got Nunavik in 1912 from the Quebec boundaries extension act. Basically they laid claim to the land of Nunavik, of Northern Quebec, what’s now called Northern Quebec, but they refused to take responsibility for the people who lived on those lands, so it became a grey area, because Inuit weren’t part of the Indian Act, so we didn’t live on reserves, at the same time we weren’t part of Quebec.

Quebec actually fought Canada in court over this issue in the 1920s and they won, with the court ruling that the Inuit were the federal government’s responsibility and the Federal Government, since they didn’t have any economic interests on the land, they couldn’t have any economic interests on the land, they didn’t have as much interest in the people either and the Inuit in northern Quebec, ended-up being some of the most impoverished Inuit in Inuit Nunangat, which means Inuit territory. So I know Inuit from Alaska, from North West Territories, from Nunavut, from Nunavik and from Nunatsiavut in Labrador, and I could see that, there’s a striking difference in regards to how the Inuit have been treated here and the types of resources they have.

One of the research projects I worked on called Nunuleavawak, was basically started because Inuit started to notice that the amount of services in Ottawa are so much more than services in Montreal. The cities are so close to each other and the Inuit populations at the time were similar, yet Ottawa has so much. There is an Inuit cultural centre, an employment center, a jumpstart program, day care, a low cost housing program, they have a healthcare facility, all that for the Inuit community and up until recently Montreal has had not much at all and Ottawa has had these things for decades.

And here just to underline, that you mentioned before, that the Inuit community has been asking clearly for a long time for an Inuit cultural centre in Montreal …

Yes. I have been to some urban Inuit strategy planning meetings where we met with representatives from Makivik and different government organizations and the Inuit here from what I can see, even just from the One Voice report from a little over 10 years ago, have been asking for a place to gather, a place to come to and I see that happening with other cultural communities in the city, there’s a German cultural center, there was a lot of discussion around the Black cultural centre being torn down and the history of that place, how that cultural center helped raised two world renowned pianists, Osacr Petterson and Oliver Jones.

So I don’t think that these cultural centres, these community centres are just a place for people to gather, but they’re also a place where people can find their passion, can find their hobbies, a place where people can feel secure with their identity amongst other people from their own community and those passions, or hobbies, can turn into careers I think.

I think that one of the problems here is that for example the services offered to homeless Inuit are often base level services, to try to get people off the street, to try to get people food and shelter, but once someone has shelter and food, what’s the next step ? And if you don’t have the next step for them, then often times many fall back into old habits and they might even fall back into being homeless again, so it becomes this cycle you know. And I don’t see a lot of that cycle being addressed here, so now there are some services here for Inuit who are homeless, for food and shelter and things like that, but what about ways to address what will happen next ? What about for things like helping people find a job, what about for higher education and I think that’s another area that the community or cultural centre could really address is, well what happens when you want to socialize, what happens if you want to build healthy relationships with people in the community ?

I guess to go full circle, going back to the ways that Inuit culture is represented but without context, so you’re talking about the actual lived realities and the very real struggles that the community is facing. But going full circle, it seems there is this consistent effort to highlight Inuit culture, but it’s done in a way that is actually void of the actual people.

Yes, like I remember that I have seen articles, especially from Radio-Canada, where they talk about Inuit, but they don’t talk with Inuit, so articles about Inuit artists, where they talk about the Inuit artist but then they talk to someone else about that Inuk. They don’t talk directly with Inuit, so that’s really the issue here, is that when it comes to the reality, Inuit aren’t being included in the society, when it comes to Inuit issues, we don’t get to talk to journalists, we don’t actually have our voices heard in the city and also we aren’t included in many of these institutions who use our identity to promote themselves, like Ungava Gin, they said that they hired two Inuit a year for four weeks to pick all the botanicals they need to produce their gin which they sell worldwide, I don’t know how they are able to do that, but at the sametime, no Inuk has come forward to say, oh well that’s my job, while many Inuit institutions like Avataq Cultural Institute Institute and even some of the municipal governments in the north, as well as Makivik, have said, we don’t know how this is happening, who they are contracting, if they are contracting anybody in the north.

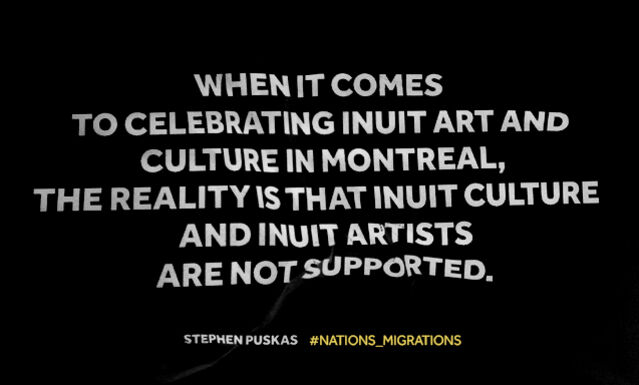

So I think there is a lot of misrepresentation happening where these companies and institutions represent Inuit without our consent, without our knowledge and without our input. Another aspect is that when it comes to arts and culture, you know I was looking into SODEC, Quebec’s cultural funder, they haven’t given any money to Northern Quebec, which is the Inuit and Cree region, nothing from 2010-2016, I checked their budgets and they had nothing in there. Quebec Arts council gave around 50,000$ from a budget of around $80,000,000 to Northern Quebec and that’s about .1% of their yearly budget, but .1% of the yearly budget for .5% of Quebec’s population, so if you’re looking at it from a population basis, Inuit and Cree in Northern Quebec are getting one-fifth, as compared to others artists, but when it comes to SODEC, with a budget of around $60,000,000, they basically get nothing. So when it comes to celebrating Inuit art and culture in this city, the reality is that Inuit culture and Inuit artists are not supported.

//

*#ComfortableTruths are mainstream attitudes and ideas about nationhood, belonging and identity that, despite not being true (such as “immigrants have it easy in Canada”), have become so engrained in the Canadian imaginary and mainstream culture that they become orthodoxy. As part of Cinema Politica’s Nations & Migrations project we reached out to activists and artists across the country and asked them to share their thoughts and reactions to these so-called truths.